7 Common VBA Mistakes to Avoid

September 21, 2017

When it comes to VBA, it’s almost too easy to make a mistake. These mistakes can cost you greatly, both in time and in frustration. I’ve seen a lot of mistakes being made in VBA code when I go to forums like StackOverflow or CodeReview. Often, they are the same mistakes over and over again. So in this post, I’d like to help you avoid these typical mistakes and make you a better VBA programmer. Let’s get started.

#1 - Using .Select / .Activate

Did you know that you don’t really need to use .Select or .Activate? It’s

understandable why people use this, they see it generated when they use the

Macro Recorder. However, 99.9% of the time it’s unnecessary.

Why?

2 Reasons:

- You cause the workbook to repaint the screen. Whenever you do Sheets(“Sheet1”).Activate, if Sheet1 is not the active worksheet, then Excel has to make it so, which will cause Excel to redraw the screen to show Sheet1. This is inefficient and will lead to slower macros.

- It will confuse the user because you are manipulating the workbook while they

are using it. Some users might think that they’re being hacked like in those

90s computer hacking movies…

Public Sub StopUsingSelectAndActivate()

Dim ws As Worksheet

Set ws = Sheet1

ws.Activate ' unnecessary

Dim target As Range

Set target = Sheet1.Range("A1")

target.Select ' unnecessary

target.Value = "Hi"

End SubThe only time you would ever want to use .Select or .Activate is if you want

to bring your user to a specific worksheet / cell for some kind of input (or

maybe if you were making a tutorial workbook). Otherwise, just delete any line

of code that uses these; their doing more harm than good.

#2 - Using the Variant Type

Another VBA mistake is when you think you’re using one Type, but really you’re using another.

Public Sub NotUsingTheRightType()

Dim a, b, c As Long

Debug.Print TypeName(a) ' Empty

Debug.Print TypeName(b) ' Empty

Debug.Print TypeName(c) ' Long

a = "hi"

b = True

c = 1

Debug.Print TypeName(a) ' String

Debug.Print TypeName(b) ' Boolean

Debug.Print TypeName(c) ' Long

a = 1

Debug.Print TypeName(a) ' Integer

End SubIf you saw the following code, would you think that a, b, and c are all of

type Long?

Dim a, b, c as LongWell, they’re not. a and b are of type Variant which means that they can

be any type and the can change from one type to another.

Having any variable be of type Variant is dangerous because they are known to

cause hard-to-find bugs in your VBA code. Avoid Variant variables as much as

you can. There are some functions that require Variant and sometimes you just

have to deal with it, but if you can help it, avoid them at all costs.

#3 - Not Using Application.ScreenUpdating = False

Whenever you make changes to any cells, Excel will update / repaint the screen to show those changes. This actually can make your macros much slower than they need to be.

The next time you create a macro, consider adding the following lines to your VBA:

Public Sub MakeCodeFaster()

Application.ScreenUpdating = False

' do some stuff

' Always remember to reset this setting back!

Application.ScreenUpdating = True

End SubCheck this post for more details on Application.ScreenUpdating.

#4 - Referencing the Worksheet Name With a String

It’s pretty much the standard to see people referencing worksheet names in VBA by using a string. Take a look at the following:

Public Sub SheetReferenceExample()

Dim ws As Worksheet

Set ws = Sheets("Sheet1")

Debug.Print ws.Name

End SubSeems harmless, right? For the most part, it is.

However, imagine that you hand off this workbook to Steve in accounting. Being a

good samaritan, Steve sees the worksheet name “Sheet1” and wants to give it a

more meaningful name like “Report.” Steve changes the worksheet name, then he

tries to run your macro that was using Sheets("Sheet1") and now it doesn’t

work.

A simple fix for this is to reference the sheet through the object directly,

rather than through the Sheets collection.

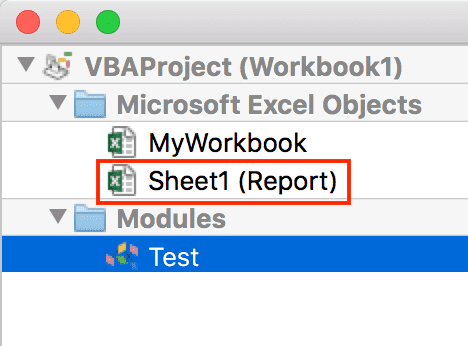

In the VBE, if you look in the Project window, you can see the worksheets and their proper names available to you.

The sheet name that people see in Excel is “Report” where the object name you

can reference in VBA is Sheet1. Let’s update the code to be more resilient.

Public Sub SheetReferenceExample()

Dim ws As Worksheet

Set ws = Sheet1 ' used to be Sheets("Sheet1")

Debug.Print ws.Name

End SubNow, we use Sheet1 rather than Sheets("Sheet1").

However, what if you want to make this name more meaningful? What if you want

Sheet1 to be something like Data?

After we renamed the Sheet1 object to Report, we also had to update the VBA

code, of course. When we ran the code, you can see in the Immediate Window that

the worksheet name was “Report” like Steve had renamed it to.

#5 - Not Fully Qualifying Your Range References

There’s a very common bug that people run into once in a while that can be a real pain to debug. This bug happens when the VBA code does not fully qualify its range reference.

What do I mean by qualify the range reference?

When you have code like Range("A1") which worksheet do you think this is

referring to?

It’s referring to the ActiveSheet, which means the worksheet that is currently

being viewed by the user.

Most of the time, this is harmless. However, over time, you tend to add more features to your code and it takes longer to process. When your user (or maybe even you) run your code and then you click on another worksheet, you will get unexpected behavior.

This is a bit of a contrived example, but it illustrates the point:

Public Sub FullyQualifyReferences()

Dim fillRange As Range

Set fillRange = Range("A1:B5")

Dim cell As Range

For Each cell In fillRange

Range(cell.Address) = cell.Address

Application.Wait (Now + TimeValue("0:00:01"))

DoEvents

Next cell

End SubHere is the code in action:

When you use Range() without specifying the worksheet, Excel must assume it’s

the active sheet. The way around this is to fully qualify your worksheet:

Simply change this:

Range(cell.Address) = cell.AddressTo this:

Data.Range(cell.Address) = cell.AddressWhere Data is the sheet object (see above). I know there are other ways around

this for this specific code example (like fillRange is already referencing the

correct worksheet), but I just wanted to make the point without adding too much

code.

#6 - Making Your Sub / Function TOO LONG

The other day I did some consulting work for a workbook I created about 10 years

ago. One of my functions was so large that I had to scroll…then scroll…then

scroll some more until I reached the end of the Sub.

A rule of thumb is that if your function cannot fit on your screen without

scrolling, then it’s definitely too long. I will make an entire post on how to

organize your VBA code, but for now, try to keep your Sub and Function

methods short by creating helper functions / sub procedures.

For a great resource on this topic, I highly recommend Clean Code by Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob). The writing is excellent and his methods of keeping your code clean are virtually timeless.

#7 - Going Down the Nested For / If Rabbit Hole

No lie, just the other day, I saw some VBA code that had 9 levels of nesting in it…9!!!! The amount of indenting needed was enough that you needed to scroll to the right just to see the code!

If you’re not familiar with what I mean by nesting, here’s an example:

Public Sub WayTooMuchNesting()

Dim updateRange As Range

Set updateRange = Sheet2.Range("B2:B50")

Dim cell As Range

For Each cell In updateRange

If (cell.Value > 1) Then

If (cell.Value < 100) Then

If (cell.Offset(0, 1).Value = "2x Cost") Then

cell.Value = cell.Value * 2

Else

' do nothing

End If

End If

End If

Next cell

End SubThis is not good, clean code.

Once you’ve hit 3+ levels of nesting, you’ve simply gone too far.

Again, I’ll make a whole post about digging deep into cleaning up code like this, but for now, here’s a simple trick you can use to reduce your nesting.

Invert your If condition. What do I mean by this? Right now, the code only

changes a value if a bunch of If statements pass. We can invert this so that

if we make the If statement check for the opposite case, we will just skip the

cell to update entirely.

Here’s an updated version of the code:

Public Sub ReducedNesting()

Dim updateRange As Range

Set updateRange = Sheet2.Range("B2:B50")

Dim cell As Range

For Each cell In updateRange

If (cell.Value <= 1) Then GoTo NextCell

If (cell.Value >= 100) Then GoTo NextCell

If (cell.Offset(0, 1).Value <> "2x Cost") Then GoTo NextCell

cell.Value = cell.Value * 2

NextCell:

Next cell

End SubObviously, I could also combine these If statements, but I just wanted to

illustrate a point.

Now, I’m not crazy about using labels, but in this case, it’s worth considering and actually made the code cleaner overall (and shorter, too!).

What are some mistakes that you’ve seen before? Share them in the comments below!